A home that’s not a home

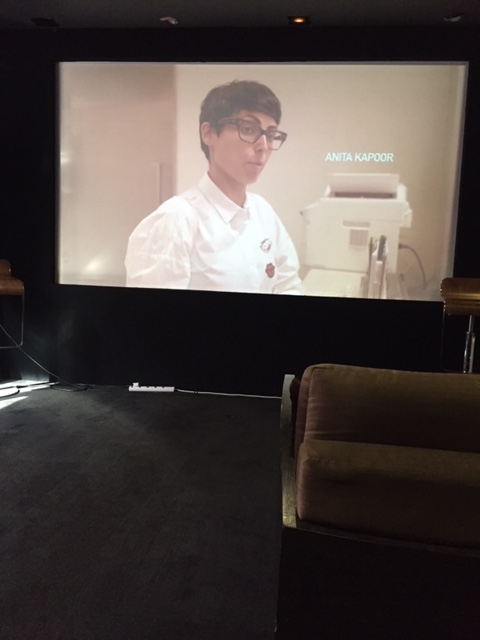

TV personality Anita Kapoor experienced two weeks in a nursing home and sheds light on the need for improvements.

Imagine living in a nursing home for two weeks. “Most people don’t think about nursing homes and many don’t know what it is like living in a nursing home,” said Lee Poh Wah, CEO of Lien Foundation. That is exactly what TV host and caregiver Anita Kapoor did when she volunteered to be a resident at The Salvation Army’s Peacehaven Nursing Home in October last year. Her experience was detailed in a 70-minute social documentary titled Anita’s Nursing Home Stay, where she went through both highs and lows.

To gain realistic insights into what the frail residents went through each day, Anita was treated like someone who could not walk, had difficulty swallowing, was incontinent and had mild dementia. She moved around in a wheelchair, slept in a six-bed ward, was woken up at the crack of dawn, got washed in a shower trolley, ate functional food twice a day and wore adult diapers for a week. And, to find out what it was like to have severe dementia and a high risk of falling like some of the 400-residents there (60 to 70 percent are patients with dementia), Anita was tied to her bed for a few nights, with the help of a body jacket to prevent falls. She also experienced wearing large mittens, another form of restraints, which is used as a last resort to prevent self-harm such as scratching or pulling out feeding tubes.

Shared Low Mui Lang, executive director of The Salvation Army’s Peacehaven Nursing Home, “This documentary project allows us to have another perspective of the nursing home experience from the eyes of a user. Although Anita is not a typical nursing home resident with dementia, some of her observations from her stay underscore the complex questions we face in nursing homes today like certain support aids have to be used in order to protect the residents’ well-being. It’s always a delicate balance between the need for safety and the downsides of over-protection.”

She added: “Through this exercise, we hope to educate the public on the reality of care provided in nursing homes today in light of financial and manpower constraints. When there’s better understanding, we can develop a common set of expectations, responsibilities and aspirations for our journey towards higher standards of care.” Peacehaven Nursing Home is open to innovation and has rolled out sensors on beds and lower beds to reduce fall risk in its home.

Far from being a home

Anita who is also a caregiver to her 73-year-old mother, who has suffered two strokes that has impaired her cognitive function, shared that what it boils down to is a re-look of the way nursing homes are run. The 45-year-old said: “We’re too system and logic-oriented, and don’t pay much heed to the heart.” During her stay, she was struck by how everything is decided for the residents, eroding individual dignity.

“I feel care has been whittled down to a regimented schedule that is not necessarily in the best interests of the residents or for that matter, the professional caregivers. Residents are existing, not living; staff are too bogged down by routine. We need to pause to ask our elderly what they want, what their feelings are. We need to stop treating the elderly and eldercare simply as beds and bodies. This, at the end of the day, is about people.”

Despite being filmed in one of Singapore’s better-run homes, the documentary surfaces several areas that nursing homes could improve, starting with the physical environment which continues to be over-medicalised. Anita highlighted the rows of beds, ubiquitous wheelchairs and the lack of privacy for residents making a nursing home more a hospital than a home. For instance, staying in a six-bed ward, she had a small bedside cabinet which had barely much room for her personal belongings. She said, “There’s no privacy, there is nowhere to hang your clothes, there is nowhere to put your pictures, there is nowhere to be you.”

A common refrain that Anita heard whenever a resident stood up was a staff asking, “Hey, where are you going? Where are you going?” She added: “Because it’s natural and I take that first as good instincts on the part of the staff here … They always know where everyone is, but at the same time it diminishes your instincts and diminishes your response. It’s a hard, hard thing right …?”

While her stay was temporary, many residents are not so lucky and live in nursing homes for years. Some do so not because of heavy nursing needs, but because they lack the social support to be cared at home. With a growing single population that is also ageing, many will end up being cared for in a home. According to a local study of six homes, 15 percent of residents lived at the homes for a decade or more and nearly half stayed for between three and nine years.

Sharing further about her experience, Anita said: “It was the hardest thing to do in my life [staying in a nursing home] but the most fulfilling. It was a personal and emotional experience. If happening to me, it is happening to others. I found it difficult to talk to my mom about what I experienced.” She added that her mother would not have wanted to see her suffer.

Restrain on restraints

The Q&A at the preview, from left to right: Anthony Tham from Zoo Group; Low Mui Lang of The Salvation Army’s Peacehaven Nursing Home; Gabriel Lim, Lien Foundation; Anita Kapoor; and Michelle Chua, Plug + Play Productions. The documentary was produced by Zoo Group and Plug + Play Productions.

Despite continued improvements and many new nursing homes being built, some nursing home practices such as the use of restraints, albeit as a last resort are still stuck in the past. Anita called the body jacket, something “like Medieval torture”, and such restraints are non-existent in some countries. For instance, in countries like Australia, simple alternatives to tying down residents – such as lowering the height of beds, thereby reducing the risk of falls – have been used for years.

Shared Dr Philip Yap, senior consultant/director, Geriatric Centre, Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, in Lien Foundation’s report, “Safe and Soulless”, “There is too much emphasis on safety to prevent falls, so the quality of life, well-being and autonomy of the resident are significantly compromised.”

Anita also observed this delicate balance in how daily routines of bathing, feeding and cleaning up were run efficiently, and goals and schedules had to be met. And, even though several residents refused their food, they were still fed. She shared, “When there is no hope, we check out. It is depressing.” Anita added that she felt “institutionalised” and after a week into her stay, she became withdrawn. After coming out of the nursing home, she suffered from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) and shared that she still has not fully recovered.

Sparking conversations

The documentary hopes to raise awareness and spark conversations on ways to improve the quality of life in nursing homes. Lien Foundation has also initiated a consumer charter which puts forward suggestions for a more evolved philosophy of care that residents can hope to get in years to come. It also suggests the rights and responsibilities of the residents and covers key areas such as residents should have a home-like environment with more personal space, residents should decide on their own care and living preferences as long as their cognitive and physical abilities allow, residents should be respected as individuals and be able to pursue their own interests, and nursing home fees and charges to be published online.

According to Lien Foundation, most public hospitals in Singapore have their own charters, but is unheard of in the nursing home sector. There are around 12,000 residents living in Singapore’s 70-odd nursing homes and the number is expected to rise. Several new nursing homes have been built in recent years and another 5,000 beds are slated by 2020. The public can comment on the charter at www.nursinghomes.sg. You can view the documentary below:

“We need to pause to ask our elderly what they want, what their feelings are. We need to stop treating the elderly and eldercare simply as beds and bodies.”

It’s one thing to comment as a fully healthy adult from a stay experience in a nursing home, but another thing to comment from a dementia patient in a nursing home. Such experience is totally different. For one thing, Anita admits that 60-70% of the patients are suffering from dementia. That being the case, how can the caretaker ask them what kind of caregiving they prefer? Dementia makes one to be childlike & have no clues of what is going on in the environment. How then can they give their preference to the caretakers? Ridiculous, agreed? It simply means they have to be taken care of like how children are taken care of, period. Nothing more & nothing less.

Thanks, Stephen for your comment, you made a good point. By the way, Anita didn’t say 60 to 70 percent are patients who have dementia, it is the information provided. And just because a person has dementia, that doesn’t mean he or she shouldn’t be treated properly either.

Sometimes, it’s not that the kids don’t care, they are too busy fending for themselves.