New clues on how ageing alters brain cells’ ability to maintain memory

NTU scientists found that communication among brain cells is disrupted with ageing and this can begin in middle age.

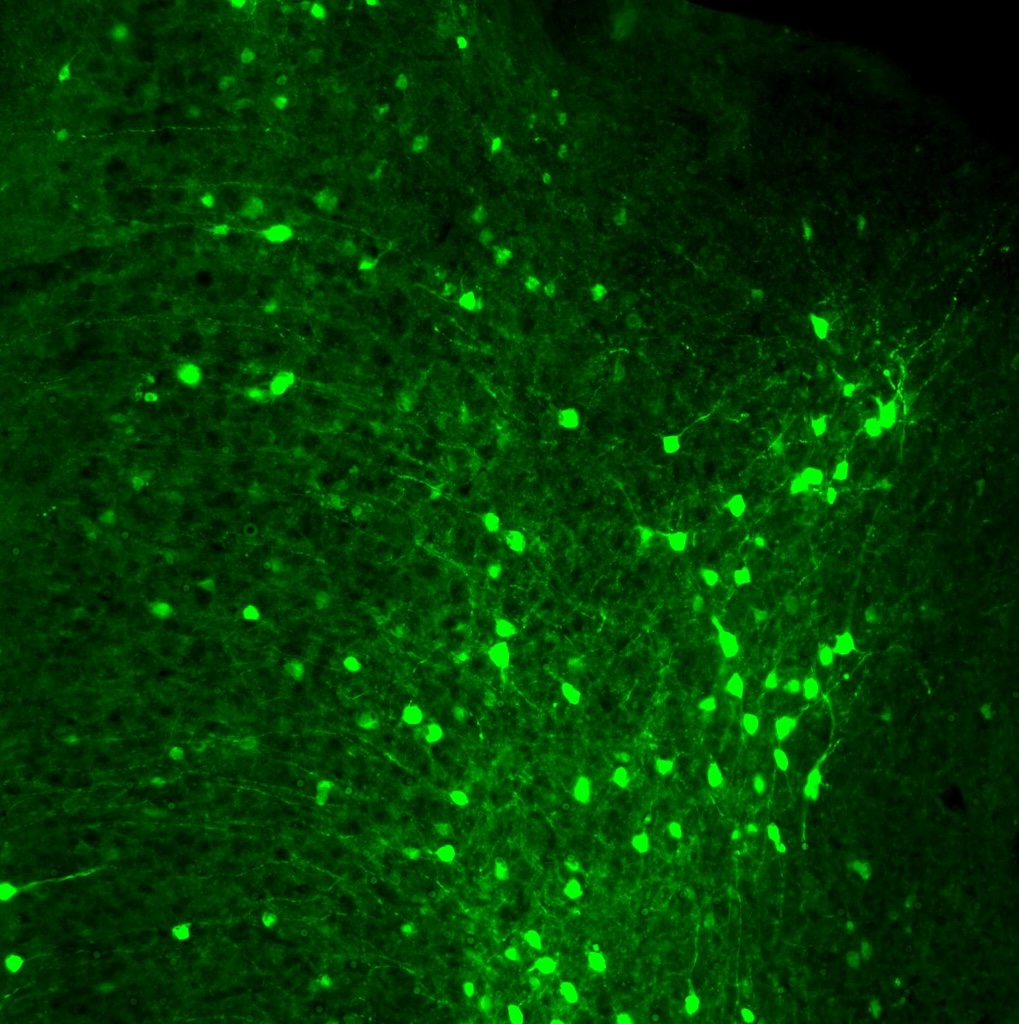

Excitatory neurons in the prefrontal cortex are shown in a fluorescent shade.

A team of scientists from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU SIngapore) has demonstrated that communication among memory-coding neurons – nerve cells in the brain responsible for maintaining working memory – is disrupted with ageing and that this can begin in middle age.

Findings from the study, which was reported in Nature Communications, provide new insights into the ageing process of the human mind, and pave the way for therapies to maintain the mental well-being of an ageing individual.

Scientists have long studied the impact of ageing on the brain’s executive functions, such as poorer self-control and working memory. While it is well-established that memory can worsen as people age, it has not been clear what changes occur at the individual brain neuron level to cause this – until now.

Previous studies used nerve cells from dead subjects, but the Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine (LKCMedicine) team measured the real-time activity of individual nerve cells in live mice. To make these measurements, the team adopted a recently unveiled optical imaging technique that allowed them to understand the function of each neuron by measuring its neural activity in the context of working memory.

In lab experiments, the NTU scientists investigated how neurons in mice of three different age groups – young, middle age and old age – responded to tasks that required memory.

The researchers showed that compared to young mice, middle-aged and old mice required more training sessions to learn new tasks, indicating some decline in memory and learning abilities from middle age. But beyond that, they also found changes in the nerve cells of older mice.

Using advanced optical techniques (calcium imaging and optogenetic manipulation) that allow researchers to observe multiple individual neurons and manipulate their activity, the NTU team discovered that neurons in one part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, showed robust memory coding ability in young mice. However, this ability to hold memory diminishes in middle-aged and old mice due to weakening connections among the neurons, which causes the mice to take longer to recall and perform tasks.

While scientists know connections between neurons are crucial for storing memory, it has not previously been experimentally demonstrated in the live brain how ageing brain cell changes cause weakening connections.

The findings thus suggest that strengthening the weakened connections between the nerve cells, such as through memory training activities, could help delay the deterioration of people’s working memories as they age.

Lead investigator and Asst Prof Tsukasa Kamigaki from NTU’s LKCMedicine said, “Our study highlights a significant reduction in communication among neurons responsible for encoding memories in the prefrontal cortex – a key factor in age-related working memory decline, which was a neurological process not widely understood until now. This discovery provides more evidence that proactive intervention can improve neuron communication. Examples of intervention include lifestyle changes such as cognitive training and regular exercise. These activities can potentially mitigate the impact of cognitive ageing and enhance people’s overall cognitive health as they age.”

Further experiments also showed that the weakening connections between the nerve cells led to instability of neural circuits in the prefrontal cortex from as early as middle age, resulting in poorer ability to hold memory.

The NTU team used optogenetic technology – a method that uses genetically engineered light-sensitive ion channels in neurons which enables the control of neuronal activity through light stimulation – to briefly turn off neurons in the brain for one to two seconds and found that the working memory circuits in middle-aged mice are particularly sensitive to the short interruptions in neural activity.

Co-first author and LKCMedicine research assistant Huee Ru Chong said, “Our four-year study shows that the ongoing function of the prefrontal circuits is critical for memory tasks. The fact that the brain circuits showed signs of degradation from middle age highlights the need for clinical strategies to safeguard our mental well-being as early as possible.”

Co-first author and LKCMedicine research fellow Dr Yadollah Ranjbar-Slamloo said, “We found that the prefrontal cortex in mice stays active when they remember things, like humans. The finding suggests that mice could be a good model for studying how memory works and its ageing process. Our findings, therefore, indicate that just as in mice, our brain may start to degrade early on as we age.”

Added LKCMedicine Assoc Prof Nagaendran Kandiah, visiting senior consultant neurologist at the National University Hospital and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital, who is not involved in the study, said, “In humans, the prefrontal cortex plays a key role in organisation, retention, and retrieval of memory. The exciting findings from the NTU team provides insights into specific neural changes in the prefrontal cortex associated with ageing. This new knowledge will be of huge clinical relevance in designing cognitive interventions to delay age-related memory decline.”

The next steps for this project are to investigate more brain-wide neural changes that occur during middle age to understand how proactive interventions may enhance communication among different brain areas.

(** PHOTO CREDIT: NTU Singapore)

0 Comments