Separated by sea & sky

Sixty-nine-year-old father of two and a grandfather of four opens up on his poignant story about his long-lost father and how today, he is closer to his children and grandchildren.

BY: James Kwok

In the late 1930s, my father, Mok Lam, was among the Hong Kong naval base technicians sent to work in Singapore’s naval base fortifications against a possible Japanese naval invasion. While in Singapore, he got to know my mother’s eldest brother, Tuck Sung, and he became a friend of the family. Back in Hong Kong, he had a wife, two sons, a mother, five brothers (excluding himself) and a sister. He was the number two son and a handy man of the family – he would fix a lot of things as the family couldn’t afford a plumber, electrician or carpenter.

War broke out in 1941 and Hong Kong and Singapore fell to Japanese bombing. After the British returned in September 1945, my father tried to locate his family through the Singapore and Hong Kong naval bases. News came from Hong Kong that his family’s village was bombed, with no survivors. This news left him devastated and depressed, and my maternal grandma nursed him back to health and got him to marry her youngest daughter, who was at the time only 17 years old. My father was at the time 38, as I later found out from my birth certificate.

My mother was very wild and my grandmother wanted a mature man to tame her. (Later, she would ride a BSA Matchless 350cc motorbike!) He already knew the family and my grandmother found him a good catch and so my mother and father got married towards the end of 1945.

Summoned back to Hong Kong

In August 1947, news came that his Hong Kong family (his father had died a long time ago and his mother remained very close to him) actually survived the bombing and wanted him to come home. He then had to make a tough decision. His decision was to bring his heavily pregnant wife, my mother, back to Hong Kong on a rickety boat. However, my grandmother said no. She was concerned that even if her daughter survived the trip to Hong Kong, she didn’t know how she might be treated there. For the family in Hong Kong, it would mean an extra mouth to feed, plus a newborn.

So he had to go by my grandmother’s idea – go back to Hong Kong and leave his Singapore family. In agreeing, he asked my grandmother for one favour – to name his child. If it was a boy, he would be called hoi thin (meaning “separated by sea and sky” in Cantonese) and if a girl, she would be named yin fun (which meant “forever separation”). She agreed and he left for Hong Kong. I was born that following month when he had already gone. The only picture that I had of him was a wedding picture of my parents. Besides the picture, my mother told me that my father had died. As long as my grandmother was around, I couldn’t talk about him.

Interesting side note, when I was five I had kidney disease and regular coughs, colds, sore throats and high fever. My grandmother brought me to see a traditional herbalist who talked to a Taoist priest, who said that my name – sea and sky – was too offensive to the spirits and decided I had to get another name. It was not the usual pig, dog or cow, but a worm (ah chong). To say the least, it did not do a lot to my self-esteem! However, I was able to go through school with no health problems.

After my grandmother passed away in 1963, my uncle Tuck Sung was doing machining work for ship engines and had a customer called Mr Chan Tim from Hong Kong who worked for a shipping company that gave my uncle work. Later, Mr Chan became a friend. In 1965, after a dinner at my house my mother asked Mr Chan about a Hong Kong address she had. He said yes, he knew of the address and they ended up conversing. At the time, I was doing my ‘A’ levels homework in the kitchen.

One month later, when Mr Chan was back in Singapore, with more jobs for my uncle, after dinner at our place, he chatted with my mother. After Mr Chan left to return to Hong Kong, I was then told what was happening. My mother revealed that my father was indeed alive and the Hong Kong address was actually where she was sending her correspondence to my father all those years without her mother knowing. This was done through the Chinatown letter writers (they wrote letters for the semi-literate and the illiterate for a fee). In Hong Kong, it was told to me that my father’s first wife also did not know about the correspondence, as the address used was my father’s younger brother’s address. Maybe deep in my parents’ hearts, they thought some day there would be a reunion.

The fateful meeting

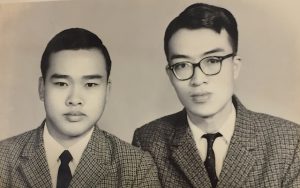

I was quite immune to all these things, there was no reaction when I found out my father still existed. I was kind of insulated and I didn’t really care. He did however send S$1,000 to fly me to Hong Kong and asked that the remaining amount of S$300 be given to my mother. On December 4, 1965, at the Hong Kong International Airport at Kai Tak, I met my father for the first time in my life. He was holding my photo while I was holding his photo. I didn’t know how to react and it was hard for me to call him “father” after so many years.

That night, he brought me to see his mother. I remembered that though wheelchair-bound, she was mentally alert, had sharp eyes, and spoke with authority. The neighbourhood called her “little tigress”. She had single-handedly brought up six sons and a daughter after her husband died. After I went on my knees to serve her tea, she pulled me aside and gave me the best instruction – she pointed to my father and said he is her second son and therefore, I must call him “Second Uncle”. I was relieved to hear this.

I spent a month in Hong Kong and my father told me his side of the story and gradually we bonded. I enjoyed listening to his Hong Kong Cantonese accent and expressions, which sounded exactly like in the Hong Kong Cantonese drama and sitcoms that I had been absorbing through Rediffusion Singapore. He worked at the time for the Hong Kong Aircraft Co (a subsidiary of Cathay Pacific Airways). He walked from his home to his workshop where he introduced me to his colleagues as his son. Through the very cold and dry December, with chilling winds humming in my ears, I got to listen to his story. I empathised with him as well as my mother. He really had no choice. Back in Hong Kong, he was lucky to get a job, where he could work two shifts for the family. But, on reflection later, I could see the effects on his family by him being an absentee father.

Of his two elder sons, the older one died of infection during the war. His second son survived from meningitis, but was not good in his studies and ended up as a messenger in a bank in Hong Kong. During the visit, I behaved very respectfully to my father’s first wife, who accepted me as her son and later accepted my mother as her sister. She said she was grateful to my grandmother who looked after her husband. The connections I made with my two half-brothers and three half-sisters, and cousins too, have continued till today.

After effects

After my visit there, my father and his wife would fly to Singapore by Cathay Pacific Airways, paying only 10 percent as he was under their employment. And, the following year, my mother and I would go to Hong Kong. We thus got to see each other each year.

Between visits, we kept in touch by correspondence. In 1991, my mother died from cancer in her early 60s and my father’s first wife died eight years later, while he died in 2001 of old age. Twelve years earlier, he had a stroke and was disabled. One year before he died, my wife, our two daughters and I went to see him at the Tai Po Hospital, where he was receiving rehabilitative care. His mind was still lucid, and he laughed and joked with my children. Pretty much, all was forgiven and our relationship was as good as it could be.

The whole thing about having a missing father didn’t affect me much growing up, as it was common during the time to grow up without a father after the war. My own two daughters went through hard times as I was struggling even though I worked for MNCs as every few years, or even months, I had to work under new bosses who came with their own ideas and agendas. If I sensed that nothing would ever please my new boss, then I knew I would have to move on.

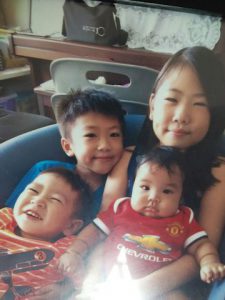

One after another, my two daughters attended universities in Singapore, and then went to University of Melbourne for further studies. I stayed at the hostel with them for the week before they began their terms, and – like how my father bonded with me for a month – I had ‘heart talks’ with my girls for a week. My grandfathering role has also helped me get even closer to them. As an Asian father, it is hard to tell my girls that I love them, but very much easier for me, as a grandpa, to cuddle my grandchildren and tell them how much I love them.

One of the grandchildren stays with my wife and me while the rest of them I see everyday after school. Being semi-retired now, I can give them the time, attention and love that I couldn’t give my children. I am grateful that when I had to deal with bread and butter issues, my dear wife was able to keep the family together. Even today, her skills and experience as a nurse are called upon, when our daughters and their friends ask her for advice with their children’s health-related issues. May we, as seniors, continue to be useful in our communities.

Currently, James is keeping busy with counselling training and motivational speaking since 2006. A teacher for 10 years in physical education (1966-76), he is a firm believer in keeping active till you drop.

Hi James,

Though Emily and I know you and Alice for more than 20 years?

This is the first time I read about your life history.

It’s obvious your life is guided by our all powerful God that you could trace your complicated family history and your parents could meet up!

Your story is inspiring and your perseverance is amicable.

All glory to our loving God,