The tontine fund manager

Tontines were a common practice a long time ago. A senior and her daughter share how they were involved in it.

BY: Eleanor Yap

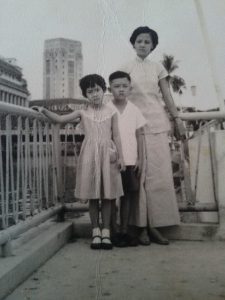

Foong Wai Chung, 90, was a fiery tontine fund manager back in the 1950s and 60s, and unlike her mother who was also a tontine fund manager, she was lucky that she never had members absconding with the money. She credits it to picking her members from only reliable people among friends, neighbours, colleagues and relatives.

A tontine group consisted of a group of members who pay a monthly subscription ranging from S$20 to S$100 every month, depending on how much they could afford. If members needed money for anything from starting a business or paying rent, to paying for schoolbooks for their children, they could secretly put in their bids to the fund manager. On a fixed date, the fund manager would then open the bids and the successful bidder will be the one willing to pay the highest interest to the other members for letting him use the month’s subscription pool.

So for illustration purposes, there was a fund of $50 subscription with 20 members. If A bid S$49, B bid $48 and C bid $47, C would be the successful bidder because it meant that C was willing to pay the other members interest of S$3 each to use their subscriptions while A and B were willing to pay only S$1 and S$2 respectively. C would therefore get only S$47 x 19, which was S$893. From this amount, C would also have to deduct S$25 (half the amount of the monthly subscription) as “commission” to the fund manager, meaning the total would then be S$868. C would then become a ‘dead’ member and would be ineligible to bid for use of the funds again. But he would still have to pay the maximum premium of S$50 every month for the next 19 months.

Should the next member successfully bid for S$49, he would collect S$50 + (S$49 X 18) – $25, a sum of S$907. If a person was not in need of the money, he would wait until the last bidding where he would collect S$50 each from the 19 ‘dead’ members, making a total of S$925, after the deduction of S$25 to the fund manager. He therefore gained interests from Bid 1 all the way to Bid 19. At the end, the fund would close and a new one would be started should there be sufficient members who want to participate. Today, this practice remains illegal.

In Wai Chung’s case, she used to run her funds by having her members put in their bids in the form of the interest they would be willing to pay the others. In the above illustration, C would have put in a bid of S$3, while A and B would have bid S$1 and S$2 respectively, as according to her, that was the practice in the community she lived in.

Ageless Online speaks to Wai Chung and her daughter, 63-year-old Carena Chor, about tontines and the stories behind this activity:

How many years were you a tontine fund manager?

Wai Chung: I was a tontine fund manager for more than 20 years and I usually managed about 20 to 30 members in each of my three funds, which ran concurrently.

How much on an average were you earning each month?

Wai Chung: I had a one $20 fund and two $30 funds. My commission would be come to $40 a month.

How did you become a tontine fund manager?

Wai Chung: My mother was a tontine fund manager and was a very easy-going person. As a result, she had been cheated a couple of times when members disappeared after successful bidding. As the fund manager, she had to then pay the missing shares on their behalf.

Because of this, I decided to take over from her, as I was not as trusting as she was and would be more careful about whom to admit as members. My mother was widowed in her late 20s and ran tontines to supplement her income, but she only did it for a few years.

As for me, I was a single mother with two children and was working as a compositor, doing type setting and so I too had to make extra money in order to make ends meet.

It was time consuming having to go round to collect subscriptions from members before I could hand the money over to the successful bidder each month. It helped that most of my members were neighbours or colleagues. I could then collect from them quite easily. Also, some of the same people belonged to more than one of my funds so I could collect for several funds.

How were you involved in your mother’s “work”?

Carena: In my primary school days, I had to collect some of the subscriptions on her behalf, as she was only free to do so after work. But she would usually ask me to go to places in the Chinatown area where we lived. The furthest she had ever sent me to was Kampong Bahru. It was then considered quite a distance from Chinatown and to make sure nobody knew I was carrying so much money, she taught me to hide the money in a tiffin carrier.

Once, it was raining and she gave me bus fare for the trip. But I wanted to save the money so I walked. Because my mother was managing three funds concurrently, the legwork was tedious. Sometimes, we had to go two to three times as there was no telephone at that time and we would not know if the members were at home. Sometimes, even when we got them at home, they would say they hadn’t gotten their salary yet.

Wai Chung: I had to keep good records of the members, successful bidders, the bid amounts, when each fund started and ended, etc.

Any interesting stories related to your tontine members?

Carena: Sometimes, the well-to-do members who attended the opening of bids would ask me to do massages by pounding their aching legs or backs with my fists. I got to earn some extra money from that.

Wai Chung: A businessman in a S$20 fund who was already a successful bidder passed away when there were four more monthly subscriptions to be made. His schoolteacher daughter agreed to pay but at the instigation of her neighbours, went back on her words. There was no written agreement so in the end I had to cough up the S$80.

I paid it secretly to maintain the trust in the group and to show that the fund would continue to operate with no hiccups.

Why did you stop and did you consider letting your daughter continue?

Wai Chung: The children were grown up so my financial burden became lighter.

No, I didn’t want my daughter to have to go through all that to make money. That’s why I made sure she had an education.

Ya, I remember my mum used to organise such tontine too in the ’60s. The first round always go to my mum. Needless to say we had a good family dinner on such days.

The bidding format is also interesting. My mum will open the bid written in wrapped paper either from left to right or right to left with a throw of a dice.