Growing up the traditional way

Jeffrey Eng may not have had much choice when it came to his future, but looking back, he is glad to be on the path that was paved by his father and grandfather.

BY: Eleanor Yap

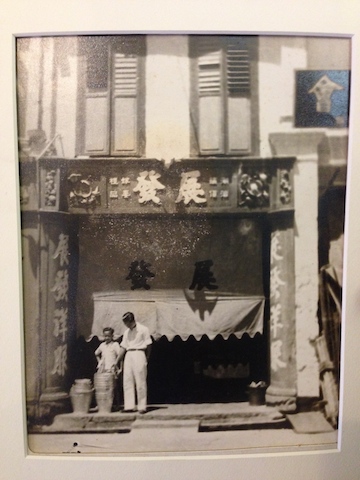

Jeffrey Eng's grandfather's shop at Merchant Road. Seen here is his father standing next to an unknown adult.

It was serendipitous in a way for Jeffrey Eng. Since he grew up in a family of sewers – his father and his grandfather were involved in it; it was a natural progression for him to go that same route. Originally, working on textiles was not something he wanted anything to do with or take over the family business, but he did and he slowly grew passionate about it.

The 54-year-old shared that it all started with his grandfather, Eng Tiang Huat (a namesake Jeffrey said he appreciated when he was older). As he felt Singapore was a better place to be than in China as a farmer, Tiang Huat ended up working as a sailor on-board a British ship and even did some cooking. His ship officer loved his cooking so much so that he was asked to be the officer’s personal cook and as a result, he got to travel up and down from China to Singapore.

He came to Singapore in 1935 and started peddling goods he got from Teochew, China like linen tapestries for pillowcases, tablecloths and bed sheets, mostly in the Chinatown area. Said Jeffrey, “They were in such demand, they were good priced and they were used by those with middle- and high-income. They were luxury items.”

A love for Singapore

His grandfather liked Singapore so much that he went back to China and sold his farm, left his family (wife, three children and three brothers) behind until things were more settled and came back to Singapore. Then he bought a shophouse in the late 1930s at 15 Merchant Rd (today, it is the road leading to the CTE tunnel). “It was a tough time as there was no place to stay and my grandmother and the family ended up staying at a relative’s place in China. However, the relative kicked them out and they ended up staying by the roadside. My grandfather had written letters to China and they never got passed down to my grandmother,” shared Jeffrey. Eventually, another relative put pity on them and took the family in.

In 1946, his grandfather’s family (without the brothers) came over to Singapore (Jeffrey’s father was 12 at the time). The shop at Merchant Road survived a harrowing Japanese Occupation. “Bombs were dropping everywhere and we were so blessed that the shop stood in one piece.” Besides selling tapestries, his grandfather started doing tailoring to supplement his income.

Pictures of his family (from left to right): Jeffrey's father Eng Song Leng, great-grandfather Eng Mong Peng and grandfather Eng Tiang Huat.

Jeffrey said that his ah kong was very sociable and because he often sailed back to China every so often to visit relatives, different people like those in the opera would ask him to buy equipment for them. “As a result of him sourcing, he ended up getting a lot of contacts and brought in more tapestries for stage people as well as musical instruments and stage props.” Tiang Huat even employed a clerk/accountant, shop assistants, handcraftsmen and a cook.

However, later on he had to stop tailoring. Jeffrey shared that coolies (or unskilled labourers) in the area would often con his grandfather and ended up not paying him for their tailoring so he stopped to concentrate fully on the Chinese tapestries. His father started to learn from the craftsmen that his grandfather hired and took over the business when he was in his early 20s. He would write to suppliers in different parts of China to source for musical instruments as well as tapestries.

Jeffrey remembered that the shop was also a sundry shop, selling even items like money belts and leather sandals from Thailand. “We even sold aluminium charcoal steamboats and Teochew wedding dowry items. It was like a regular department store as one thing often lead to another!” said Jeffrey. “We also sold joss pots and religious products but not the joss sticks and incense paper. My grandfather was also against selling idols (statues) as he felt we couldn’t sell God. He had his own principles about being respectful and I continued this today.”

And even though the shop closed at 7pm, the door panels still were opened and people continued to stream in. And once when his grandfather bought an RCA TV set, children as well as his friends would come to the house to watch. “My grandfather would brew tea and I was tasked to buy kopi and tin cigarettes. His friends all sat in the same positions, smoking and drinking. It was like a community and very neighbourly, not like what it is today.”

The move to River Valley

In 1982 when Merchant Road was under resettlement and after his grandfather’s passing at the age of 72, Jeffrey’s father moved the shop to 284 River Valley Rd.

“The garang gunis would complain that we didn’t leave anything for them. My father even sawed off the old staircase railing. If he could he would have taken the roof! He took everything.”

They also found a lot of treasures thanks to the move. “There was an old safe and we found more treasures inside including a piece of paper selling my grandfather’s land in China, title deeds of the Merchant Road shop, etc. I did searches on the Internet and learned about the history during those old days. I got to know more about my roots,” said Jeffrey.

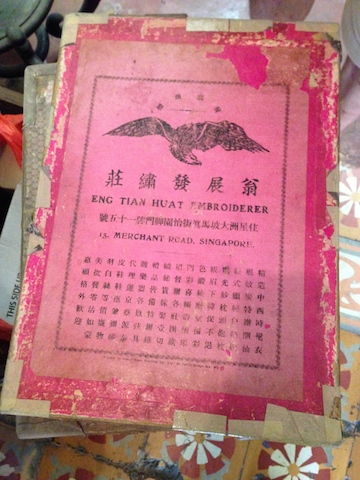

He revealed he has kept everything – from his grandfather’s first store wrapping paper and store catalogue to an old telephone from the store – and he has stored them in a warehouse as well as in the current shop at Geylang Road. “It is good to keep as one day my children’s children might want to know where I come from.”

Jeffrey said that as he grew up, he learned a lot about the family business. “Craftsmanship must see-and-watch; it can’t be learned overnight. I sometimes asked questions and my father would answer. There is no class; it is all hands-on. If I made a mistake, he would get angry and sometimes laugh it off.” Jeffrey was not keen in being a part of the family’s business, what he used to term as an “old-fashioned trade”.

However, after National Service when he wanted to do something he liked, his father was steadfast and said no, and persuaded him to join the business. He agreed. “I started sewing and stitching, and became passionate about it. I felt a heavy responsibility to carry on the business when my father died in 1994, as my siblings were not interested and also my grandfather and father had wished to carry on the business. If I didn’t carry on, I felt it would have offended my grandfather and father. They had built something for me and my siblings,” said Jeffrey. He said that currently none of his three daughters are willing to carry on the business, with one of them running her own cake shop.

Tougher times today

He shifted a year ago to where he is today at 10 Lorong 24A Geylang and he still continues the quality craftsmanship that has been passed down. But today, times are very different. “During my grandfather’s and father’s time, there were a lot of customers ordering customised pieces including the red banners before Chinese New Year. Today, there is only a handful and some of them are two to three generations. It is sad to see that the trade is dying out.”

Jeffrey explained that a customised embroidery alter cloth, for instance, can take one month to complete and cost around S$1,200. He will help add in special touches on the embroidery such as motifs that could be from the 1950s, which he kept from his grandfather’s time, and shared he has only two to three pieces and if used up, he would be hard-pressed to find more.

He also still supplies Chinese cultural products including musical instruments, opera props, costumes, weapons, etc, and shared that he is the only shop carrying dialect musical instruments. He doesn’t import large quantities from China but he does do repairs. “I still have swords and sabres that are 30 to 40 years old. Customers come and look for me for the old stuff. The newer stuff can be easily bought in China.” For an older opera costume, it can cost over S$3,000. He has two to three sets left in his shop from his grandfather’s and father’s time. He also assists with alterations.

His shop looks like a museum where boxes piled high could reveal more interesting items from his past. Said Jeffrey: “I told my children not to throw any of the stuff away or if they have to, to give them to someone who can treasure our history so they can carry our story forward.” The path he chose may not have been his choice early on, but he has come to appreciate all things from his past as well as his business.

Very interesting article. I have recently sold a hammered ducimer that was purchased in 1982 from a shop at No15, Merchant Road. Judging by your story and the details on the receipt, I believe it may have been the original shop you mention in the article.

If there is any interest in such memorabilia, I can send photos of the instrument and an image of the original receipt and of a small advertising poster for the shop.

Co-incidentally, the young man who bought the dulcimer is from Singapore although he grew up in Australia.

I can be contacted at the email address I have submitted below.

Thanks for your comment, that is very interesting indeed.